Meinir Jones / GP / UK

Dr Meinir Jones, a GP from South Wales, has had a varied and exciting career, but in 2014 faced her most significant challenge yet: as the medic on a crossing of the polar ice cap. Testing enough, you might think, but this expedition was in support of Pete Bowker, a military veteran aiming to be the first amputee to cross the Greenland ice sheet unsupported. She tells us of the grit of her team mates, the joy of bacon, and the importance of a GSOH on expedition.

As a GP with a special interest in sports and musculoskeletal medicine, having spent several years as a middle grade in busy trauma centres across the globe, my career has often followed the path less travelled. Putting my hand up, trying new things, and letting the monkey out of its box has allowed me fantastic, memorable experiences. To date, these include being a ski doctor, cruise ship medic, V8 supercar medic, and covering the Olympic and Commonwealth Games. Next up, ‘settling’ with my young family into primary care medicine and dipping my hand intermittently into pitch-side cover and mountain running. Little did I know during my first meeting with Richie Morgan, Team Leader for 65 Degrees North, in a small but well known coffee house in Swansea back in the summer of 2014, three small words would seal my fate as the on-ice doctor for the team that crossed the Greenland ice cap. Expedition naïve, the only female and non-military person, “I can ski” were the words that made me the 5th and final team member for what was to become my biggest challenge yet.

‘When someone offers you an amazing opportunity and you are not sure you can do it, say yes – then learn how to do it later’ – Richard Branson.

Background

Greenland has the world’s second largest ice cap, with over 600km of skiing from west to east, the threat of polar bears, crevasses, weather-enforced tent days, and temperatures of down to minus 40. In 2013 Peter Bowker, a 28yr old lower leg amputee and veteran from Afghanistan, decided to attempt to be the first amputee to complete an unsupported crossing of the ice.

Why Greenland? Pete had been about to leave the Army when he was given the opportunity to do his adventure training, and was informed he would be one of several crew sailing from Iceland to Greenland. Destination reached, and perched on a rock in Scoresbysund looking across the ice-cap, Pete made himself a promise that he would one day become the world’s first amputee to cross the ice on skis.

What followed was a slow and frustrating start, with dyslexia floundering his attempts to gain support and funding, and little in the way of replies to his emails and letters. Following the Hero’s Challenge in 2013, he forged a friendship with Richie Morgan, an ex-Royal Marine and serving police officer, who helped the project gather momentum and support. Within 18 months, funding had been secured from LIBOR, and endorsement gained from the Royal Foundation. A meeting with Prince Harry in November helped increase the media footprint and credibility for the project.

Pre-Expedition Medical

I have always been a firm believer that when seeking knowledge, you should speak to those with experience. You learn far more than from books. I spent time with several very experienced expedition medics, devised a ‘kit list’ which was vetted by Dr Dan Roiz de Sa (Doctor for Walking with the Wounded) and Dr Ian Davis (who has completed more expeditions than I have fingers and toes) and weeded everything down to a 4kg pack of essentials for the 28 day crossing. Their first-hand experiences were invaluable in preparing me and my team for what lay ahead. I also sought advice from Dr Nick Webborn, who has a wealth of experience in dealing with disabled athletes, and pointed me in the right direction for expert help with stump care and tissue viability.

“So who looks after the doctor when the doc goes down?” How do you prepare for that? I made it my job to ensure that everyone was capable in times of need. I printed laminated sheets of ‘How To’ manage common medical problems, within a clearly labelled, colour-coordinated kit bag.

Medicine on the Ice

I recorded everyone’s sleep, mood and resting heart rate, as well as daily injury/illness/concerns in the back of my diary. This would help me better anticipate any subtle changes which might have led to bigger problems, allowing me to act quickly to try to prevent the latter.

Pete’s stump rapidly broke down with the extreme conditions and increasing physical and mental demands of 12-hour days’ skiing. His analgesic requirements increased as we progressed and I opted to issue him with regular medication, rather than give him analgesia on an as required basis, which helped to keep him going. The pain, though not verbalised, was all too visible in his altered biomechanics and difficulty skiing.

He lost a lot of muscle mass around the stump as time went on, revealing new pressure areas throughout the crossing. This posed new challenges due to altered fit of the prosthesis which consequently affected his ski technique, giving him lower back and shoulder pain.

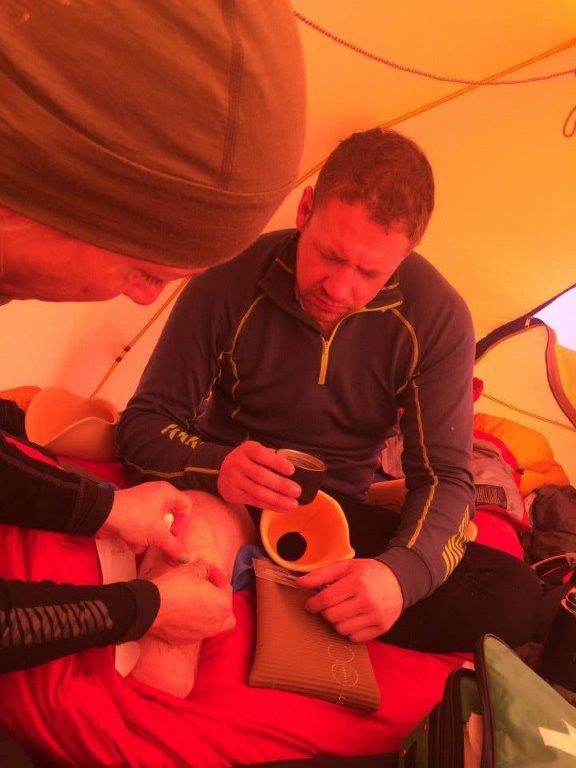

Daily ward rounds, wound management, stump inspections and blister care were the norm, with frequent alterations of Pete’s prosthesis using scalpels and nail files. Sjur Modre, our Norwegian guide, was able to use his carpentry skills in altering the socket, allowing for the subtle changes in the areas on Pete’s stump prone to pressure.

Foot care for everyone was vital, with taping to avoid blisters: they could be game-changing for the expedition, hindering our progress across the ice. The team had been advised to learn how to tape their feet before the expedition, and most of us were able to keep the same tape on for the duration.

Tent-enforced days due to poor weather conditions were a double-edged sword, delaying our progress but allowing much needed time for Pete’s wounds and stump to heal.

Challenges

Training

Pre-expedition work out: tyre pulling, weighted walking, mountain running – I even invested in a cross-country ski machine. The key was to spend time on your feet, with plenty of strength training thrown in. This was a real juggling act, with a full-time job and two young children with a busy social life of their own. A training week in Norway a few months before our May departure helped get the team up to speed with tent skills, pulk-packing and navigation: a mini expedition that helped give us a flavour of what lay ahead. It also helped team-bonding. We learned each other’s strengths and, maybe more importantly, our weaknesses, which really helped to prepare us for the challenge in Greenland.

Toiletting

The weather conditions necessitated learning to empty your bladder into a wide necked vessel whilst kneeling in a down sleeping bag. Imodium was my friend during the tent-enforced days of severe weather, of which there were several! Some top tips were given to me by Kate Philp, whom I met in the months leading up to Greenland. Kate was one of the team who completed the South Pole challenge with Help for Heroes with Prince Harry.

Nutrition

In order to keep going for the 10-12 hours of skiing, we ate protein-infused porridge for breakfast and snacked on protein bars, digestive biscuits, nuts and dried fruit. For our evening meal we ate reconstituted dehydrated Norwegian army scran. Luckily for us, Sjur, one of Norway’s finest guides, supplied a daily fix of bacon, camp-cooked muffins, and even smoked salmon on rye. This came from his Mary Poppins pulk bag, bringing much needed treats out like party tricks to keep morale afloat. I had advised the team to take probiotics for the month leading up to departure, to help build immunity and reduce the risk of gut upset. This, after blisters, is the second commonest cause of medical issues in such extreme environments.

Navigation

Navigating was often very challenging, especially in white out conditions. It was frustrating to watch as the worm of team members, following the nominated ‘worm’s head’, ended up back where we started. Especially when pulling a pulk weighing more than me! It was a real lesson in resilience. We used sastrugi lines in the snow to navigate, and if we were lucky, the sun cast shadows on them allowing us to follow an angle set out by our guide. It is so easy to get lost when everything in front of you is white, just white. We all took turns in navigating, with some faring better than others. It could be very demoralising when distance covered by skis didn’t correlate to the distance from our start to end-point. Straight lines turned into ‘wiggly worms’ when visibility was low.

A predicted 18-19 day crossing turned into 28 increasingly longer days, due to poor conditions. A highlight of my day was my daily diary entries, and reading the comments left by close friends and family, randomly placed on the otherwise blank pages. Poems from my daughter, funny stories from a friend, and even 21 single daily notes from my ‘bestie’ helped to trigger memories which filled my mind during the hour of skiing between 10 minute breaks.

Our evening communal dinners in Sjur’s tent were a real coming together, with Pete’s humour and the team’s recollection of their time in the military fuelling laughter and discussion. The pièce de résistance was a tiny map of the crossing that Sjur would carefully unfold and plot our whereabouts on, signalling progress across the ice cap.

The Inmarsat beacon gave us an invaluable connection to home, and provided an immensely important link with the outside world. It provided daily updates, and increased Pete’s media footprint in raising awareness and much needed funds for his nominated charity, Help for Heroes.

Final day dramas

With just over 40km skied that day, and only another two miles to reach our destination, Kirk ran into difficulties and found himself down a crevasse. It was a very hairy moment indeed, but demonstrated teamwork at its best, with me on camera duties to capture the moment. Crevasse rescue successful, we completed the day’s skiing roped up, and in over 2 hours laters arrived exhausted, hungry and elated.

An excerpt from my diary on the last day:-

Thursday 4th June – Zero KM left, expedition complete!

I’m sat in Kullusuq airport – with the sun warming my back awaiting our boarding call. Yesterday was a mammoth day. After a delayed start due to awaiting phone call confirmation on our travel info, we commenced on what was to be our longest day, both in mileage and hours and time on feet and in skis.

As we descended to our final campsite, Sjur edged us all forward. Was quite symbolic in fact that the team were all connected by rope. We took a few steps, then let Pete take his glory in touching the rocks – the world’s first amputee to ski across Greenland, unsupported. I think we all got a little emotional – well no surprise that I did anyhow!

I’m totally and utterly exhausted today – no sleep from sentry/polar bear watch and kit organizing! No bears were sighted but we (Mick and I) did see a little solitary Arctic fox scuttling around the camp – peeping from behind the rocks above us. He must have sniffed some of the measly rations that we ate around 0230! Several hours passed quickly at Kullusuq airport – lots of laughter and reminiscing. I think Sjur has also enjoyed the challenge, us being somewhat different from his usual group. My God, how lucky were we in having him as our guide – his ‘Mary Poppins’ pulk, his calm and wise words, his ‘knowing’ of what to do next, his carpentry skills with Pete’s prosthesis. His words of encouragement and stability.

Pete’s determination, mental resolve humour and predictability with ‘one liners’, grit and strength of character make him, in my eyes, a true hero. And so, the expedition is over, we are up in the air – high as kites literally and metaphorically and about to really face the music. Patrons, family friends and other team members await our arrival in Iceland. A team decision made not to shower! To arrive as we had finished – in kit, smelly, unkempt and weathered! My only compromise; a wet-wipe wash and clean knickers, bra and thermals. My plait brushed, hair greasier than ever and a small amount of mascara. I am good to go.

Our legs have felt like jelly today, from a combination of such a big day yesterday and so few ski-free hours on our feet over the last month. I even caught Mick trying to ‘glide’ across the airport lounge! I decided to reflect on the negative and positive aspects of the trip.

- Wind chill factor of below minus 30

- Tent enforced days

- Groundhog menus

- Toughest endurance training ever!

- A world of only men for a whole month!

- No loos

- No chairs

- No family

- Very few cwtches [welsh word for hug]

- No showers

- No fruit/veg/fresh food

- No tap

- Snowstorms

- White outs

- Great teamwork

- Camaraderie

- Some glorious sunshine days

- Great humour and craic

- ‘Pulk full of morale’

- Sjur’s treats

- Courage overcoming those so called ‘physical boundaries’

- Joy in achieving something big and helping Pete achieve his dream

- Privileged time for reflections and appreciation for the smaller things in life

- Overcoming my own fears of cold

- Fun

Homeward bound

And so what’s next? The question on so many’s lips after my return from Greenland.

Some time to pause and reflect. My involvement with the growing organisation that is 65 Degrees North continues. 65DN seek to encourage rehabilitation through adventure by inviting injured servicemen, with both physical and emotional injuries, to push boundaries, work as a team and assist their rehabilitation. It gives them back focus, not only in the present with the challenge, but also the skills to move forward in their own lives. Great support is being given by Swansea University and their team of psychologists. Mount Vinson is on the near horizon, with a team of five attempting what is oft termed the ‘Jewel in the Crown’ of the five summits. They depart January 5th. This time I am their remote medic, staying in the warmth… but who knows next time?

Lessons learned

- Trust your gut, know your team and be tenacious in gaining knowledge – knock on doors.

- Remember to keep a diary. You will forget so much, and it helps to purge any negativity and doubt on the trip.

- Don’t forget to pack the two important Hs in your pack: honesty and humour. Both essential to surviving, and enjoying such a challenge.